Whenever the latest one comes out, I always ask myself: how many books on the subject of Disney do we really need?

Whenever the latest one comes out, I always ask myself: how many books on the subject of Disney do we really need?

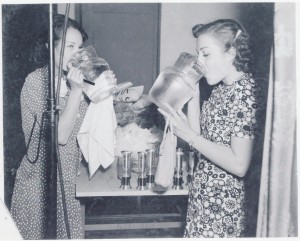

The Disney Company seems to be increasing the amount of books pumped out about its history every year, and the answer to why is simple: few other Hollywood studios have kept as pristine records as Disney has, giving the company an unprecedented advantage on the book market. It of course also continues to establish the Disney Way over other styles of animation. Big attractive, lusciously illustrated books about Disney abound, and the ones about other films keep shrinking.

More importantly, they are also ingenious at keeping readers satisfied with no more than they “need” to know. (For an excellent examination of this topic, read Michael Barrier’s piece, “The Approved Narrative.”) I commend anyone with the dexterity to undertake such a project, given how increasingly paranoid the corporate behemoth is getting these days. (Re: the delay of Amid Amidi’s Ward Kimball biography.)

I met J.B. Kaufman in 2009 at the Buffalo International Film Festival, where he was a special guest promoting his newly released South of the Border. From meeting him personally and reading his work, he strikes me as someone with an earnest appreciation of the medium’s history and one of the few able to communicate it through his writing. He told me that while he enjoyed learning everything he did and found South a rewarding experience, he was far more thrilled to start working on his new book about Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.

We should all share his enthusiasm. The Fairest One of All: The Making of Walt Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs is possibly the most welcome of all Disney Editions in recent years. With access to seemingly endless documentation, Kaufman was able to create a much-needed work: the go-to-book for the most written about and lauded animated feature.

As I’ve stated before, Snow White was not one of my favorite Disney features growing up. Its clunkiness and overlong nature was too obvious, and I was swayed by the later features’ slicker surfaces and broader comedy. Upon revisiting it several times on actual film, what resonated with me considerably more than the best acting scenes by Bill Tytla and Fred Moore was how convincingly the artists portrayed mood throughout the picture, specifically pure horror. All but a scant few pictures in this genre defy the classification of camp, but for a period of time Disney was able to get under people’s skins and emotions like few other filmmakers.

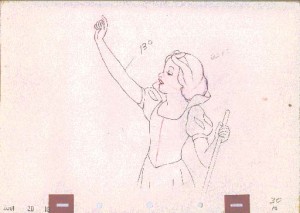

From a Bill Tytla scene, drawing appropriated from Michael Sporn’s Splog.

None of this is addressed in the book, and it of course shouldn’t be, given its topic. It’s a mark of its strength that it’s gotten me to ponder about Disney so deeply. There is a lingering problem in the text though, which I also noticed in South of the Border. Kaufman seems to be holding back, balancing positivity and negativity far too evenly. The “now it is bad, but there are some virtues” template is used far too often for any serious critical discourse to be established, probably exactly what Disney Legal had in mind. It also works in its disfavor when there clearly is a right answer, as with the far too wishy-washy coverage of the color and restoration issues with Snow White over the years. There clearly is a right way to see the film, and that is how Walt Disney delivered it to RKO in 1937. (A frame grab comparing a frame from an original 35mm nitrate to the modern DVD is below, exemplifying how the initial candlelight effect of the cottage interior has been eradicated over the years.) At the very least it should be released in that incarnation some way, let the naysayers say what they will.

Even under these conditions, Kaufman plants analyses successfully throughout the text, so that a less enlightened reader might be convinced that the animation in The Goddess of Spring is seriously bad, or that all of the Disney heroines from Cinderella on are unquestionably simpler in conception than Snow White. His fervor for the film is evident on every page. Even the seemingly most mundane aspects about the feature are brought to entertaining life. Kaufman’s writing is not condescending, free of academia, and sympathetic to an accurate portrayal of an important period of Disney history.

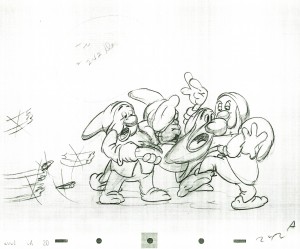

The biggest downside to this book is the utter lack of actual animation drawings, made all the more noticeable by how scrumptiously displayed the rest of the artwork is. Perhaps there was conflict using similar illustrations to those seen in the backhanded Illusion of Life. But considering how excessively detailed Kaufman’s descriptions of the contributions Tytla, Moore, Babbitt, Natwick, et. al. made to the film, what better place to show their actual drawings?

From a Grim Natwick scene.

Everything that went into making this film, be it the story meetings, the lectures from Walt, or the sheer labor in actually drawing the thing, makes for some of the most compelling writing on animation ever. Writers try to make the behind-the-scenes stories of other Disney films seem just as intriguing, but they almost never are, most likely because the hard part, actually making a watchable 80-minute cartoon feature, was already accomplished. Everything that followed after was just business as usual for the artists, thus most of the later films were never as compelling, and the studio was just fine with that. Yes, the “sincerity” remained there for awhile, but it had all but vanished by the turn of the war; certainly it’s nonexistent in today’s meaning of “Disney”. Whether anyone will actually admit that is unlikely. But Kaufman’s book is at least a reminder of the assets when sincerity in filmmaking is actually, well, sincere.

I’m curious, is that 35mm print you compare the DVD to an original from Disney’s RKO period? I’ve always been curious about how RKO was originally credited as the distributor for this film ever since getting the original two-disc DVD in the early 00’s. The ‘original’ opening title sequence was included as a bonus and appeared (to me) to be a colorization of the sequence taken from a contemporary promotional film about the Hyperion Avenue studio. But the closing “The End” title appeared (again, to my view) to have been cobbled together from the Buena Vista reissue ending and a mid-40’s reissue trailer, with a big RKO Radio Pictures logo in the background. It never seemed accurate to me.