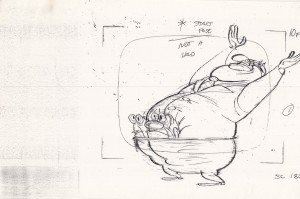

Chris Reccardi caricature drawn by Bob Jaques in 1998.

Chris Reccardi

A 2009 Interview with Thad Komorowski

When people hear of Chris Reccardi’s untimely passing from a heart attack on his surfboard in the Pacific Ocean, they might think the guy’s profession was “rockstar”. They wouldn’t be wrong. Reccardi truly was a rockstar of sorts, bringing a highly stylized point of view to current animation; the “modern graphic” look that became popular in ’90s animation is down to his and his wife Lynne Naylor’s work on Ren & Stimpy. If the style worked in a future show or feature, their names were usually somewhere in the credits. And if anyone’s portrait should hang in every major modern studio as the most influential storyboard artist of all-time, it’d be Chris Reccardi’s.

For as magnificent a cartoonist he was, Reccardi never struck me as particularly interested in cartoons (he quipped that he only liked three of them, Popeye Meets Sindbad and Dicky Moe being two; I never found out what the third one was) as he was in other art forms, specifically music, which made his approach all the more interesting. But he was certainly interested in his cartoons. I wrote about Reccardi’s work on Ren & Stimpy at length in the eleventh chapter of Sick Little Monkeys, partly because of him, too. He insisted he talk about the cartoons he directed at Games Animation as part of his agreement to do the interview, which is why so many of the questions are episode specific. This led to not just more viewings of those cartoons, but further conversations about Reccardi’s work with Mike Kim, Don Shank, David Koenigsberg, and others. I followed Reccardi’s works and words for years, always hoping he’d once again enjoy the freedom he did in the Ren & Stimpy days. That might have happened with the shorts program at Nickelodeon that he was supposed to head this year, so we can mark that as one of the great tragedies of animation history.

With years of acrimony out of the way, most viewers will agree that Reccardi’s work stands as some of the most important and intriguing of the entire series. This was an interview conducted by e-mail in September 2009, when I was still a fledgling untangling the show’s saga, so forgive some of the wording or awkward phrasing on my part. Reccardi only did a few interviews about his animation work; a longer, career-spanning interview with Hi-Fructose Magazine is at this link. This was the only one he did at length, or in-depth, to my knowledge, about Ren & Stimpy.

How did you get involved working on Ren & Stimpy?

Chris Reccardi: One of my first jobs was as a character layout artist on the new Beany & Cecil that John was producing at DIC in 1988. That’s where most of the key R&S people all became friends. John would have us over his pad most Friday evenings for “Theory night” – I guess his version of what Bob Clampett did in the early days with his crew, but mostly an excuse to drink heavily while bitching about animation and stuff. After a stint with Ralph Bakshi and Tiny Toons, R&S got picked up for series and I joined in Nov. 1990 as a storyboard artist.

What were your contributions to the show?

CR: On the actual series I started out doing storyboards, and later supervising layouts and then directing, which encompassed a lot of duties: storyboard, layouts, some music and even voices. I never wrote on the Spumco material, but was there when some of the ideas were born, like “Ren Seeks Help”, which was fun.

The takeover of the series/firing of Spumco… Most people say they saw it coming well in advance… Did you personally? Were there any particular incidents that made it obvious what was coming next?

CR: I had already left the show months before that happened, but even then, there was a lot of trouble with missed air dates. If you asked me personally, I’d say that is the biggest killer of any show. I think if the shows were being delivered on time, Nick might have forgiven the creative differences – maybe – but the combination of the two were lethal. A lot of fans and Spumco folk got caught up in the drama of “why” but at the end of the day, missed airdates are a total no-no in TV.

Since you were on the show at Spumco and Games, what would you say the differences in the working environments were?

CR: Spumco had a smaller crew and better schedule. The biggest bottleneck then and at Games was character layout. That’s where all of the acting and cool drawings happened, and John was VERY particular about how well we drew and could interpret the storyboard drawings. It was awesome training and we all learned a lot about animation, acting and drawing, but the damn TV schedule never allowed for corrections or improvisation.

At Games, there was simply less talent left from the Spumco crew, and the schedules got tighter. I think by the end of fifth season it was obvious that most of the shows weren’t going to be good and that the priority was to get them done. However, me, Mike Kim, and Tom McGrath storyboarded, laid out and directed our own shows – as one-man crews with some occasional help from the few good artists there were, and some of these maintained a very high level of quality.

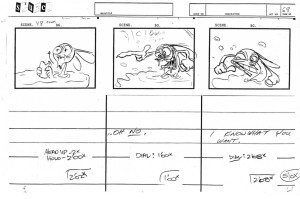

One of Chris Reccardi’s layouts for the Wilbur Cobb sequence of “Stimpy’s Cartoon Show”, which he also storyboarded.

You speak of bottlenecks at Games on the layouts…

CR: There really weren’t the same bottlenecks at Games. When they realized that they could not produce shows of Spumco-level quality in the required timeframe, there were two choices: either shit them out, or if you were a director with capable skills, lay out most of the show on your own time (nights and weekends). You can kinda see which ones are which if you have an eye for that.

Some artists had more skill and experience than others. And of course talent. Like any TV production the work load was too great for all of the episodes to be good, so those who had the most skill chose to concentrate on a few good ones, rather than be spread thin trying to save the series.

How would you describe your directorial style and process?

CR: I don’t know, I guess it was very hands-on. I hated writing, but if there was a good story, I would storyboard it, then go to layout. I felt timing was crucial, so I tried to look at every exposure sheet. I wrote a lot of my own, that way I could coordinate strong layouts with good timing. That’s where the real shit happened. Then later make sure the soundtrack worked well with it, spending a lot of time picking appropriate sound effects.

Not just your standard stuff but unusual things, like a huge castle door slamming instead of the obvious normal lame sounds that your average SFX editor might pick. I was just mostly hands-on. I’ve grown up since then and enjoy delegating more to a talented crew. You get to have a life.

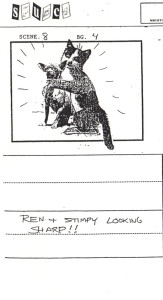

From Chris Reccardi’s storyboard for “Man’s Best Friend”. The gag of Ren and Stimpy becoming photo-realistic cat and chihuahua was credited to him.

You are credited co-directing two cartoons with John K., “Dog Show” and “Royal Canadian Kilted Yaksmen”. How did that work? How were the duties split up?

CR: At the start of season two, Vincent Waller, myself, and Bob Camp were being groomed to eventually direct in order to allow John to make the deadlines. “Dog Show” was one of the “B” stories so it was safe enough to toss my way. I supervised the layouts, and did a bunch myself, then sat with John for the voice directing and the editing. It was an apprenticeship kind of thing.

I think John is credited as co-writing most of the Spumco stuff, because he was involved with most of it. The ones he didn’t take credit for are ones he didn’t like, the throwaways. There were several shows in various states of production after the firing. “Ren’s Brain” “Cartoon Show” were written at Spumco but never produced until Games. Bob was saving “Brain” for the last season but it was finally offered to me to direct as a final, high-quality piece to wrap up season 5 with.

With “Yaksmen” I was fired off the show half way through, but did all of the post-production later at Games. I believe that show received no direction from anybody, other than the brilliant timing and animation at Carbunkle by Bob Jaques. I would say he was the real director. Back when I was storyboarding it, I really didn’t get the feel of a story for it, and John was really preoccupied with other challenges at the time. I was still learning and just just never took charge of that thing. It was supposed to be another “B” episode, but Bob Jaques made it an “A” show, at least visually.

Which were your favorite episodes that you directed at Games? The ones you were the most proud of?

CR: They all leave much to be desired nowadays, but I thought “Hermit Ren” was a great idea for a story that I wish I had another crack at. Same with “Ren’s Brain”. Those were total character-based pieces. Unfortunately I was still learning my craft and wish I had some of the skills I learned later. “A Hard Day’s Luck” was an episode without Ren & Stimpy that a lot of colleagues liked but I don’t know what the rest of the world thought. But who cares.

You started directing regularly fairly early on, but many new names began showing up in the director’s credits. Much more so than at Spumco. How did this work at Games? Who decided who would become a director? Were there specific units – i.e. a director had a certain crew of artists?

CR: Towards the end it became necessity. It became more about finding anyone capable for shepherding the remaining shows to completion. I think it came more from the producers than Bob Camp, who simply could not handle the amount of shows left. Tom McGrath began directing very soon after he began because it was obvious he was a motherfucker talent.

Would you say that you like to instill “drama” into your cartoons? “Hermit Ren”, “Yaksmen”, “Hard Times for Haggis” have a lot of it, more so than the other cartoons at Games.

CR: I would say I did what was required for those particular stories. Yes, I’ve always been attracted to psychodramas (Capatain Kirk in “The Enemy Within” and Jimmy Stewart flipping out in It’s a Wonderful Life) but those scenes were the logical result of those character’s arcs. I hate that word, but it’s required jargon in the entertainment world.

Regarding “Powdered Toastman Versus Waffle Woman”… Although you were the director on the episode, I was told Lynne Naylor supervised the layouts. Is this true?

CR: Hmmmm… not correct. Lynne came up with the idea for that show, as part of her arrangement to work at Games (to do stuff with new and alternative characters) but she didn’t do very many layouts on that one. I don’t remember why, but maybe because she left by the time that went into layout. She did the storyboard which was fantastic. I wish she laid the whole thing out!

The opening theme music… How did it come about, and who was responsible for it?

CR: Jim Smith, my buddy Scott Huml, and I had been jamming and writing music for a couple of years, and when John was doing the pilot, he wanted some crazy Chino-style music for the dog pound sequence. He also wanted some gutsy blues stuff for the title card and end credits. When the show went to series, John convinced Nick to use those two pieces for the beginning and end titles – mainly as an alternative to what might have been really dumb theme songs.

You’ve mentioned how important the music is to R&S. How did the style of it come about?

CR: It definitely started with John who understood that cartoons deserve the same attention to the soundtrack as the other elements, which I embraced as a musician. It’s not that it was more important than the other stuff, (in fact an inappropriate score can distract and wreck the story pretty easily) but it’s another important tool needed to build a successful cartoon, so I tried to be sensitive to the needs of the story. I did some music where I felt it was needed, but in hindsight I did some of it for the same reason a dog licks his balls – because I could. The other directors perhaps were not such music dorks as me and managed to pull some pretty good stuff from the library, which was an awesome library.

How did you decide on when to use stock music or original music?

CR: It depended on the episode and how immersed you needed the audience to be. I was always disappointed with some shows and how generic and predictable some of the music gets. “Sling Blade” has an incredible soundtrack by Daniel Lanois that’s this haunting collage of unrecognizable instruments and sounds, and it takes you to a deeper level of feeling. It never distracts.

So when I wanted something completely abstract, based totally on feeling, that you couldn’t find anywhere else, I would go into my home studio which had like, every instrument. Like when Ren freaks out in “Hermit” at the end. That was a bowed upright bass with wah-wah, and echo, and a hollow body fretless bass with a slide, picked way down at the bridge also with echo to create these “skittish” sounds. I wasn’t able to find shit like that in any library. It was more about creating the right atmosphere than needing to be a composer.