The release of Shout Factory’s Mr. Magoo: The Theatrical Collection is a cause for celebration. It’s been delayed for almost two years now (when I was driving home through New Jersey with one of the people who worked on transferring the negatives, he indicated that the work had been completely done ages ago), but whatever the circumstances were, it’s out and a purchase is in order.

I detect no vandalism to the cartoons I’ve viewed thus far in the way of DNR or aspect ratio distortion. I’m no expert on the UPA cartoons’ exhibition history, but the widescreen cartoons seem appropriately presented. Mark Kausler said the later cartoons on the TCM Jolly Frolics collection were “marred,” but there was no consumer outrage. Possibly because everyone had fallen asleep during the likes of Ham and Hattie and Baby Boogie, and the same may hold true for the later cartoons on this set.

As has been well established in the wake of that marvelous TCM set, the UPA cartoons worthy of the most attention and praise are those done when John Hubley was commanding the ship. Roughly the first half of the first disc of this set is from that era and they are inarguably the best, no question. In those cartoons, the sense, as Hubley intended, that Magoo would be making most of these mistakes even if he wasn’t near-sighted is easily apparent. Spellbound Hound, the second cartoon, features a scene poignant in its absurdity: Magoo is on a fishing boat and has mistaken a record player for the motor. He knows something is wrong, but he’s determined to make the record player operate as a motor, and is cheerfully triumphant when he finally gets the thing to play continuously.

As has been well established in the wake of that marvelous TCM set, the UPA cartoons worthy of the most attention and praise are those done when John Hubley was commanding the ship. Roughly the first half of the first disc of this set is from that era and they are inarguably the best, no question. In those cartoons, the sense, as Hubley intended, that Magoo would be making most of these mistakes even if he wasn’t near-sighted is easily apparent. Spellbound Hound, the second cartoon, features a scene poignant in its absurdity: Magoo is on a fishing boat and has mistaken a record player for the motor. He knows something is wrong, but he’s determined to make the record player operate as a motor, and is cheerfully triumphant when he finally gets the thing to play continuously.

The combination of character animation, humor, and modern design is in perfect balance in these first Magoos. I was struck by how well the design in Barefaced Flatfoot (by Abe Liss and Jules Engel) works to make the preposterous story (Magoo, obsessed with detective stories, is worried his nephew Waldo will get money to repair his car through ill means) even funnier by making the settings so cold and serious. Another highlight from the restoration was realizing that the crooked moving men in Bungled Bungalow are a single mass. That was an intriguing surprise, and I wish the rest of the set yielded more of them.

It’s to be expected that a set devoted to a single character is going to run on autopilot when you get deeper into it; no one with any seriousness could vouch for which Tom and Jerry, Woody Woodpecker, or Popeye cartoons of the mid-to-late ’50s are “better than average.” The real surprise here is how darn fast the Magoo cartoons coast. By the end of the first disc, Magoo has lost his edge and become a more affable coot, and the jokes take on a predictability that would make Seymour Kneitel blush. Pete Burness directed most of the Magoos, and it’s apparent his years at MGM and Warners didn’t have much of an impact on his comic sensibility. Those cartoons took on formula too, but they aren’t nearly as offensive as the ones here.

Which is sad, because it didn’t have to go downhill so quickly. As you journey forth, the cartoons not only lose the humor. As early as Captains Outrageous that calculated, studied animation Art Babbitt brought to the animals in Ragtime Bear, Grizzly Golfer, and Fuddy Duddy Buddy is gone and replaced with straight, no-frills acting. The bloodless design work becomes overwhelming, as in Magoo Express, where Magoo seems at odds with where the UPA look was heading. The cartoons become a kind of “radio noise,” material you put on in the background while doing something else in lieu of complete silence. (And that really depends on your tolerance for Jim Backus.)

Which is sad, because it didn’t have to go downhill so quickly. As you journey forth, the cartoons not only lose the humor. As early as Captains Outrageous that calculated, studied animation Art Babbitt brought to the animals in Ragtime Bear, Grizzly Golfer, and Fuddy Duddy Buddy is gone and replaced with straight, no-frills acting. The bloodless design work becomes overwhelming, as in Magoo Express, where Magoo seems at odds with where the UPA look was heading. The cartoons become a kind of “radio noise,” material you put on in the background while doing something else in lieu of complete silence. (And that really depends on your tolerance for Jim Backus.)

While watching the untitled documentary produced for the set, I was astounded that the animator Bob Longo’s comments on how the cartoons were moving away from design to just cheapness by the time of the Oscar-winning When Magoo Flew made the cut. A slip, no doubt, as most of the interviewees try to sidestep or understate that UPA introduced the concept of bad animation in service to design (good or bad) as an accepted industry practice. Make no mistake though: these guys off their course were establishing kids’ TV animation. How you can watch something like Magoo’s Moosehunt, or the feature 1001 Arabian Nights (essentially a Captain Crunch commercial in design and feel expanded to 75 minutes, but with an amazing George Duning score), without drawing that conclusion is beyond me.

While watching the untitled documentary produced for the set, I was astounded that the animator Bob Longo’s comments on how the cartoons were moving away from design to just cheapness by the time of the Oscar-winning When Magoo Flew made the cut. A slip, no doubt, as most of the interviewees try to sidestep or understate that UPA introduced the concept of bad animation in service to design (good or bad) as an accepted industry practice. Make no mistake though: these guys off their course were establishing kids’ TV animation. How you can watch something like Magoo’s Moosehunt, or the feature 1001 Arabian Nights (essentially a Captain Crunch commercial in design and feel expanded to 75 minutes, but with an amazing George Duning score), without drawing that conclusion is beyond me.

Suffice to say, you’re getting a lot for Shout Factory’s ridiculously low price of $29.93. Just think of it as getting those wonderful early cartoons with three discs of bonus features.

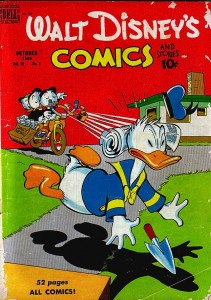

One of the books I most highly anticipate is one I can already heartily recommend: Michael Barrier’s Funnybooks: The Improbable Glories of the Best American Comic Books is set for publication at the end of December.

One of the books I most highly anticipate is one I can already heartily recommend: Michael Barrier’s Funnybooks: The Improbable Glories of the Best American Comic Books is set for publication at the end of December.

Oh, yeah, hey.

Oh, yeah, hey. I personally was anticipating Ghez’s assemblage of Homer Brightman’s memoir

I personally was anticipating Ghez’s assemblage of Homer Brightman’s memoir