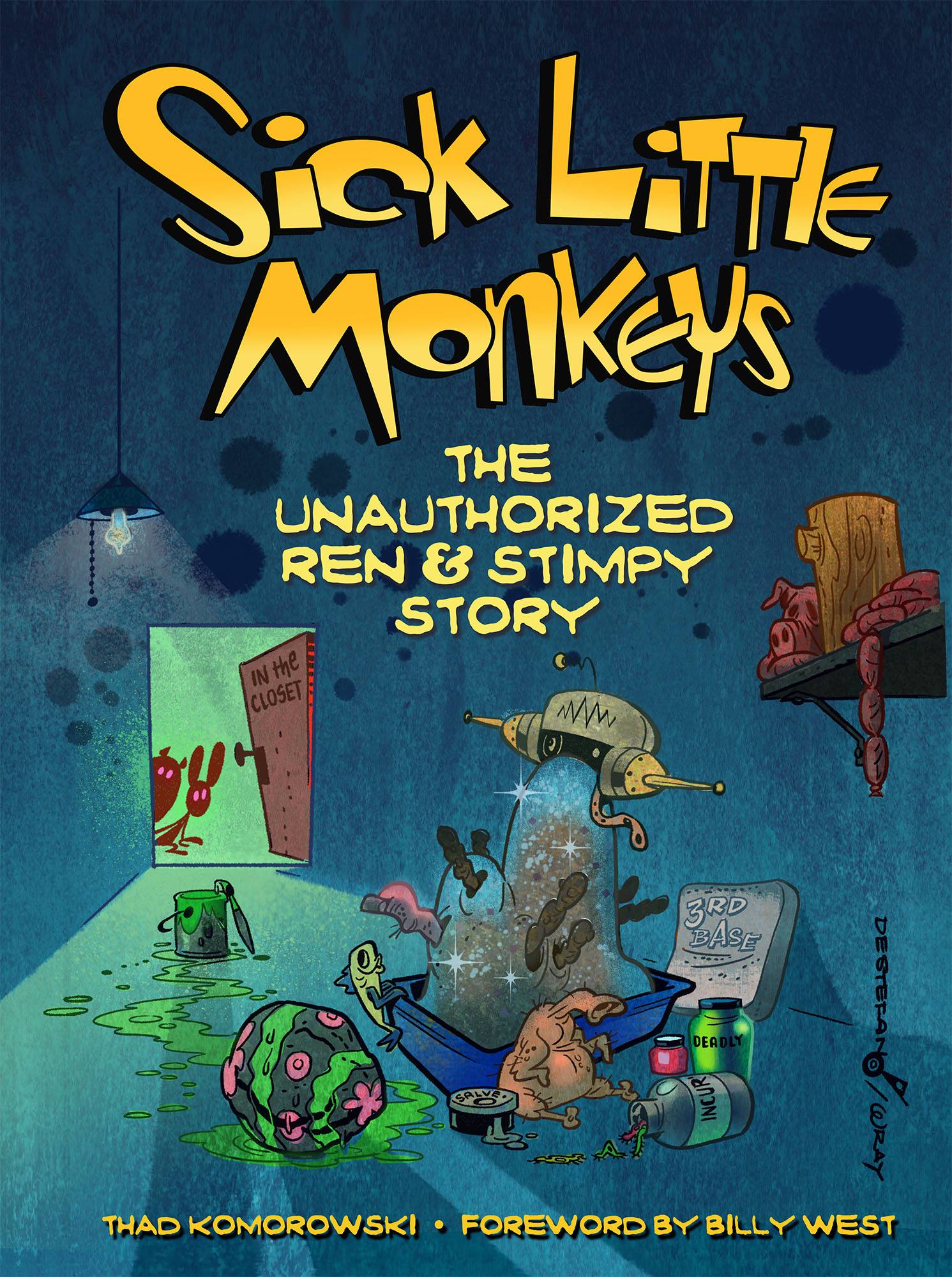

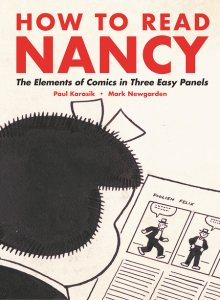

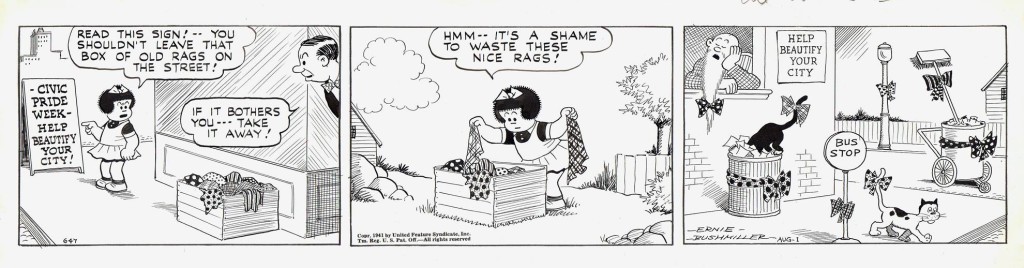

Top: the Aug. 1, 1941 strip of Ernie Bushmiller’s Nancy. Bottom: the Terrytoon School Daze, one of two failed animated shorts with Bushmiller’s Nancy and Sluggo. The adaptation of that ’41 strip starts at around 1:25. Note that the strip (which is even legible at thumbnail size) is readable in some six seconds, whereas the Terry guys ballooned the joke to some 90 seconds. The new Fantagraphics book How to Read Nancy: The Elements of Comics in Three Easy Panels doesn’t discuss why things went so wrong with the animated cartoon, unfortunately, but once you finish the book you can probably figure out why.

Full-disclosure: this review is by someone who has chided Mark Newgarden over the years for even doing his long-gestating How to Read Nancy project with Paul Karasik. Along the lines of, “How to Read Nancy? With your Eyes Wide Shut.” But I always knew if someone like Mark respects Ernie Bushmiller enough to do a 44-chapter-and-then-some intense study of him, there has to be something special at work there.

How to Read Nancy will inevitably be an important college text: its writing is engaging but never fannish, and breaks down the concepts of visual storytelling in a manner that will not turn off the average reader or student. I can easily see this becoming an alternative to Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics in many curriculums. That book has its virtues and will always be valuable, but I always thought it an awful idea for McCloud to do it as an actual comic book. Newgarden and Karasik lavishly illustrate the history and their thesis, and also understand that concepts need to be explained in words without distracting the reader with the authors’ own creative concept.

How to Read Nancy will inevitably be an important college text: its writing is engaging but never fannish, and breaks down the concepts of visual storytelling in a manner that will not turn off the average reader or student. I can easily see this becoming an alternative to Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics in many curriculums. That book has its virtues and will always be valuable, but I always thought it an awful idea for McCloud to do it as an actual comic book. Newgarden and Karasik lavishly illustrate the history and their thesis, and also understand that concepts need to be explained in words without distracting the reader with the authors’ own creative concept.

Which is the point of the book and its subject: simplicity is important, underrated, and misunderstood. Newgarden and Karasik don’t try to hide that the prevailing opinion in the comic critics world is that Bushmiller was a hack. As they said in a Comics Journal interview: “Krazy Kat and Little Nemo resemble “Art.” Peanuts resembles “Philosophy.” Nancy resembles nothing more and nothing less than a comic strip (and a gag-driven, self-proclaimed “dumb” one at that), hence: easily dismissed from the canon.”

I certainly sympathize with battling critical prejudice. Friz Freleng gets the same flak from animation fans and historians for not being as flamboyant as the other Hollywood cartoon directors, despite the simple poses and animation in his cartoons generating as many (and arguably more) laughs as anyone else’s pictures. While I didn’t leave the book thinking Nancy is some misunderstood classic that deserves the sort of attention as Herriman, Schulz, or Milt Gross’ work, the authors have certainly made their case that Bushmiller implemented intelligent design on a daily basis. And not just because of his intense gag-writing process that’s covered well here.

The fact is, a lot of comic strips were and are junk. Newgarden and Karasik are able to take a single innocuous Nancy cartoon and analyze some forty-four elements within the following categories: the strip, the script, the cast, props and special effects, costumes, production design, staging, performance, the cartoonist’s eye and hand, details, and the reader. In not one single instance does it feel like they’re reaching—the elements are all there and done well enough that they can be highlighted individually. I’m hard pressed to think of another strip simple enough to analyze cartooning principles in this depth, even my absolute favorites. Maybe a Peanuts strip, but then again, that “philosophy” would overshadow the non-philosophical lesson intended. There’s no “philosophy” at work in Nancy—just craftsmanship that delivers the goods in seconds. That certainly cannot be said for all the long-standing dinosaurs that are part of the King Features family. And that’s why the book is proving so interesting and popular: that you can mine all of this education out of a dismissible Nancy strip.

One other element of the book I particularly admired, as a fellow cartoon archaeologist, and fear will be ignored in other reviews was the historian aspect of Newgarden and Karasik’s scholarship. The story of Bushmiller—his work, his influences, and what made him tick—is covered more thoroughly here than it will be ever again. Most illuminating was the reveal that there is no complete run of the Nancy comic strip available anywhere. In fact, they didn’t even have an original copy of the 1959 strip when they started the book—nor did they know the actual date it appeared! (For the original essay, the strip was taken from a Nancy collection where it appeared undated and without the syndicate/copyright information.) Thankfully that little dilemma was solved, but the larger one remains.

Theoretically there could be a Nancy run assembled by some enterprising historian willing to go through hundreds of thousands of microfilm, but to this date that hasn’t happened. In an age where just about everything is getting reprinted, often material that doesn’t warrant it (I’m thinking of the fussy Al Taliaferro Donald Duck strip that’s getting the red carpet treatment from IDW), perhaps this tome will lead to Bushmiller getting his due. I mean, why not?

Perhaps the most profound thing reprinted in the book that makes the authors’ case is a 1959 newspaper comics page where the strip originally appeared. Even without knowing what I was looking at, my eye was drawn to Bushmiller before anything else, including the more respectable cartoons like Li’l Abner. Even if you stubbornly cling to the idea that Nancy is junk, the book is still worth reading because everything Newgarden and Karasik say can be applied to cartooning and comedy in general. The book is also important for the influence it will hopefully have on the cartoonists who read it. The medium is crowded with clutter and it remains difficult to discern those who deserve attention, whether it’s in a book or at a gallery. That doesn’t mean to draw as simplistic as Bushmiller or just go for the dumb laugh—just take a leaf out of his book so your art will stand out in the wallpaper of the cartooning world.

Now available from Fantagraphics is

Now available from Fantagraphics is