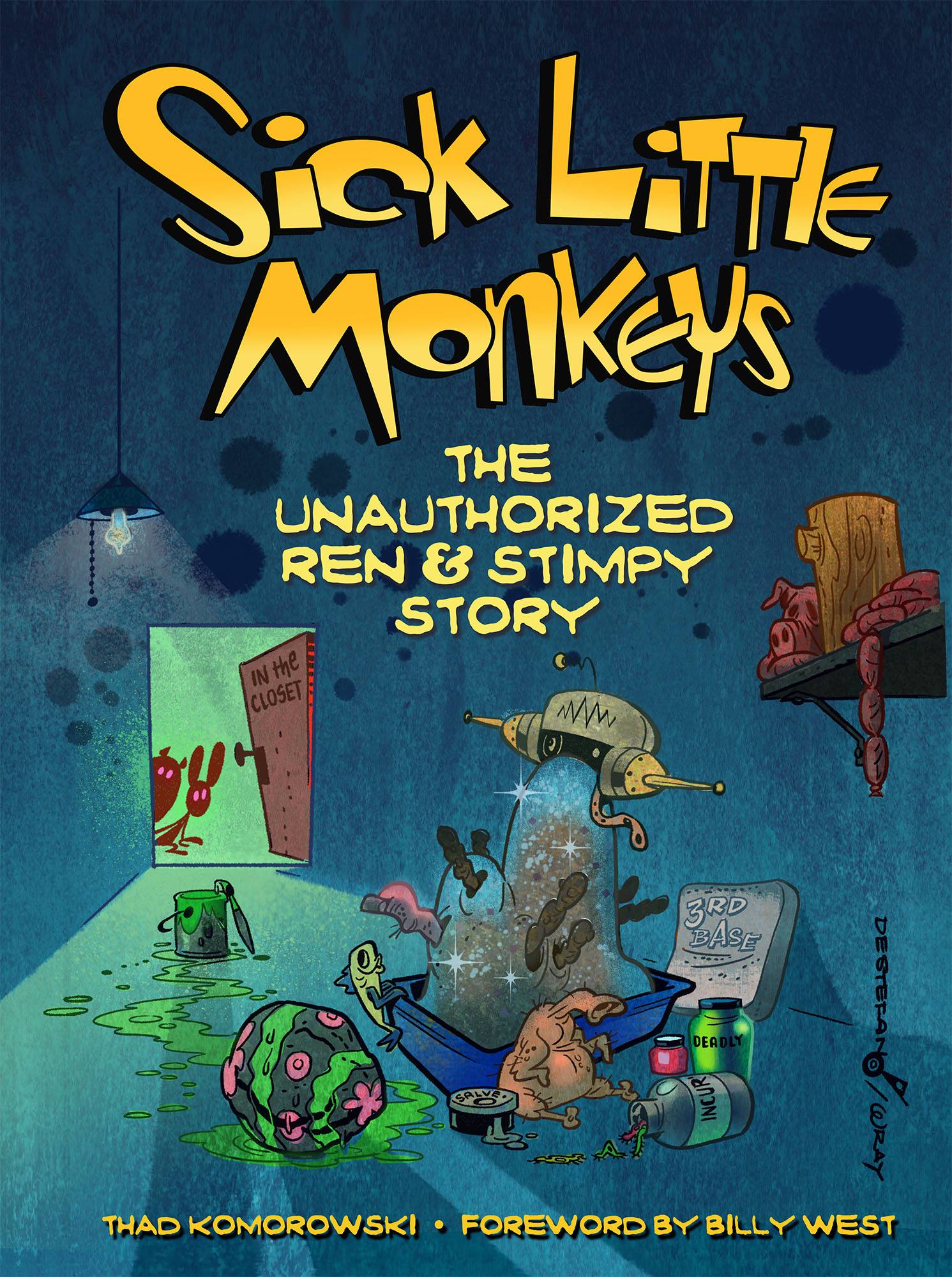

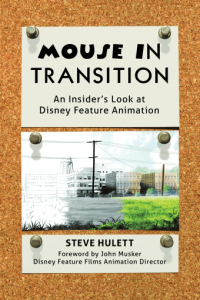

Steve Hulett’s Mouse in Transition: An Insider’s Look at Disney Feature Animation is easily the most important book Theme Park Press has published to date.

Steve Hulett’s Mouse in Transition: An Insider’s Look at Disney Feature Animation is easily the most important book Theme Park Press has published to date.

I say that with some trepidation, but I think it’s justified. Indie publisher Bob McLain has given a venue to important Disney historians like Didier Ghez and Jim Korkis to bring information to print that the Disney Company feels has little value (or doesn’t want you to know). All of those books are impeccably researched from documentation and eyewitness accounts. Whereas Hulett’s book, about his period of employment as a writer at Disney from 1976 to 1986, is written from his own firsthand experience.

That may sound like I’m condemning the memoir format, but I’m not—they can be of extreme value. Depending on the reliability of the writer, a memoir can be the only way certain information can be gleaned. While I do believe Shamus Culhane’s memoir, Talking Animals and Other People, has a number of apocryphal and self-serving accounts, it’s an invaluable document telling what it was like working in the Golden Age, and the pain so many people went through.

Likewise with Hulett’s. His accounting describes the last decade of Ron Miller’s reign on Walt Disney Productions as a backwater Hollywood studio undergoing prolonged decay, with old talents retiring and dying and new talents leaving or becoming the latest studio hacks. And by all accounts that’s exactly what the Miller era of Disney was. The least you can ask of a memoir is that it captures the feel of the period and environment accurately, and Hulett’s book does that amazingly well. Particularly given that he’s writing about vapid films like The Fox and the Hound and The Black Cauldron, two of the studio’s all-time worst.

Mouse in Transition could prove problematic, and that’s only because it may remain the only serious examination of that period of Disney. I wish the book was longer (I read the whole thing on my regular commute to Newark and a side trip to Jersey City), because Hulett’s readable, breezy narrative can muddle certain points, as with his account of Don Bluth going from a politicking M.V.P. to leading a mass exodus in under two pages. It’s also common knowledge that just about everyone was glad to see animation’s equivalent of Jim Jones go—the “betrayal” was all the other young talent leaving with him. That doesn’t come through very well in Hulett’s narrative.

Hulett’s most critical passages tend to be about people no longer with us. His vivid, stinging portraits of the designer Ken Anderson and director Woolie Reitherman certainly match others’ accounts, and how Moe Gollub led a strike against runaway production that ended in a humiliating defeat for the union in 1982 is common knowledge.

When it comes to the living, Hulett’s kid gloves are on. The storytelling is more colorful when exec heavyweights like Michael Eisner and ex-Disney Feature Animation president Peter Schneider enter and get taken to task, but any negative remark about Jeffrey Katzenberg is immediately qualified with a positive. (Got to be nice, or Jeffrey might just bribe Obama a bit more to send more work overseas.) Ron Miller disappears for chapters at a time and seems immune to scrutiny. Not that the memoir should blast every person mercilessly.

This is, after all, one man’s story and opinions, not an assembly of accounts that independently corroborate. A Disney director has told me he’d love to do a book on the period along the lines of a traditional Hollywood history, and I hope there will be others, because there’s far more to the story (one eyewitness can’t know everything that was going on in a studio). But Mouse in Transition still remains an excellent account told by someone with a deep interest in studio history. As if to prove that point, Hulett’s interviews with Ken Anderson, Claude Coats, Wilfred Jackson, Ward Kimball, Eric Larson, Don Lusk and Ken O’Connor fill out the book. (The Kimball interview is by far the most entertaining.)

I have no doubt Steve Hulett will be taken to task by other eyewitnesses and writers (just wade through the archives of the TAG blog to find he’s no stranger to controversy as The Animation Guild’s business representative), but at least that will encourage more dialogue about a largely undocumented period. We’ve gotten a choice sampler of why Walt Disney’s studio went into a deep decline after his death. Now what we need is the full-course meal (of which Mouse in Transition will certainly be part of).

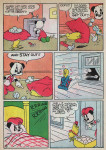

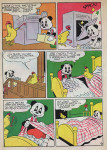

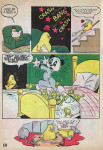

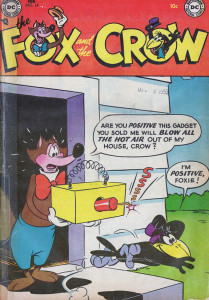

I had posted this story years ago on my now dormant site Golden Age Funnies. Like every niche website, both the proprietor and audience lost interest. My scans from at least ten years ago are long gone, and all to the good, because my skills at getting archival material online have increased tenfold.

I had posted this story years ago on my now dormant site Golden Age Funnies. Like every niche website, both the proprietor and audience lost interest. My scans from at least ten years ago are long gone, and all to the good, because my skills at getting archival material online have increased tenfold.

Steve Hulett’s Mouse in Transition: An Insider’s Look at Disney Feature Animation

Steve Hulett’s Mouse in Transition: An Insider’s Look at Disney Feature Animation