(This site may become Thadwell’s Book Corner soon, but don’t count on it.)

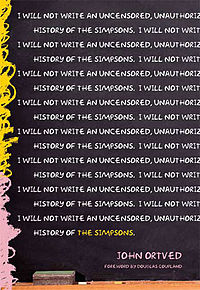

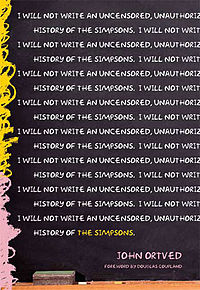

It’s been over two years since the release of John Ortved’s The Simpsons: An Unauthorized, Uncensored History. I put off reading it until very recently. The consensus is that while Ortved did a solid job researching his subject, he botched the presentation.

It’s been over two years since the release of John Ortved’s The Simpsons: An Unauthorized, Uncensored History. I put off reading it until very recently. The consensus is that while Ortved did a solid job researching his subject, he botched the presentation.

The book takes that most undemanding route of the oral history, a format indicative of a writer with zero narrative skill. The adeptness to accumulate the facts was there, as successfully conducting some eighty interviews is no mean feat, but weaving them into something compelling was beyond Ortved.

Ortved’s own prose is fannish at best. The book credits a copyeditor, but one wonders what that job entailed given how ham-fisted the final book is. (There are also many typos and grammatical errors.) Ortved presents his own anecdotes under the delusion that someone reading a history of The Simpsons is interested in his personal viewing experiences. He is also presumptuous thinking that the reader already knows who worked on which episodes; that by merely naming episode titles, his case for what exactly was “the Simpsons‘ Golden Age” is made.

The best example of the book’s shortcomings may be the entire chapter devoted to former Simpsons writer Conan O’Brien (he was one of Ortved’s more prestigious interview subjects, quoted on the back cover). O’Brien was obviously an essential presence in the writers room. Surely his best solo writing job, Marge vs. the Monorail, is one of the few perfect half-hours of 1990s television (and far funnier than anything else he’s done, up to and including the present day). Ortved never tells us why O’Brien was significant to the series. All we learn is that the other writers found him a continuous riot and that they were all amazed to see where he’s gone.

One of the chief complaints is that Ortved is too opinionated in his book. He doesn’t think too highly of the last 15 years or so of The Simpsons, and thus received poor marks for his dismissal. Of course, anyone with eyes shares his opinion of the show’s decline. Rather, the resentment should be towards how poorly he framed his critiques. Ortved’s analysis of the Simpsons‘ peak is practically nonexistent, whereas his emphasis, prose on how “lame” the later episodes are, is barely above the average Internet forum posting.

The block quotes are ultimately what you’re going to get the book for. Now that the book is less than $11 on Amazon, you could do much worse. Certainly the price is justified for people like O’Brien or Brad Bird talking about the show in detail. It’s also a great primer for those interested in learning about the show’s chief architects. The quotes give indication of how compelling a history of The Simpsons could really be.

Journalist [and Simpsons guest voice] Tom Wolfe makes a thought provoking comment near the end of the book. “The Simpsons also managed to make a virtue out of bad draftsmanship. The characters are really terribly drawn, but they are so stylized that it doesn’t make any difference any longer.”

Truer words were never spoken about the show. Fans like to romanticize about the fist few seasons, but the show was always poorly drawn and mechanically animated. What was wonderful, though, is that it was a deliberate mechanicalness, one that helped emphasize the sharp writing and the best ensemble of voice actors in decades. It was not merely what its detractors call an ink-and-paint live-action show. While owing more to live-action than any cartoon, it was still something that couldn’t work if it was not animated. When the writing was golden, they used cartoon license to add to the scripts’ quirkiness. Surely no one could envision animator David Silverman’s scenes of Homer’s heart attack or “No TV and no beer make Homer something-something” translating nearly as well into a live-action comedy; the movement is humorously stilted, becoming a new form of stylization in the process. This effect deteriorated as the show progressed, no doubt. When the writing went to pot and the voices started phoning in, there was nothing to hide the crude formula of the draftsmanship that was always present.

Truer words were never spoken about the show. Fans like to romanticize about the fist few seasons, but the show was always poorly drawn and mechanically animated. What was wonderful, though, is that it was a deliberate mechanicalness, one that helped emphasize the sharp writing and the best ensemble of voice actors in decades. It was not merely what its detractors call an ink-and-paint live-action show. While owing more to live-action than any cartoon, it was still something that couldn’t work if it was not animated. When the writing was golden, they used cartoon license to add to the scripts’ quirkiness. Surely no one could envision animator David Silverman’s scenes of Homer’s heart attack or “No TV and no beer make Homer something-something” translating nearly as well into a live-action comedy; the movement is humorously stilted, becoming a new form of stylization in the process. This effect deteriorated as the show progressed, no doubt. When the writing went to pot and the voices started phoning in, there was nothing to hide the crude formula of the draftsmanship that was always present.

In the decades since The Simpsons premiered, there have been many primetime animated shows. These shows’ creators included people who would like to be doing live-action exclusively but use drawings as a means of presenting unoriginality as hip (Mike Judge), those whose greatest talent is exploiting the growing ADHD in our society (Seth MacFarlane), and even some who enlarged upon The Simpsons‘ virtues and carried them out in a completely different way (Trey Parker/Matt Stone).

Prime time animation has not been very visually pleasing as a result, and that irks a lot of people. It’s undeniable that having people ingrained in live-action has worked in these shows’ favor. Controversial though it may be, live-action people are just plain smarter than animation people. If it were the other way around, maybe every major artist-driven series or studio wouldn’t fizzle out/peak after a couple of films/years, be it financially or artistically.

Ortved was charged with being one-sided because he didn’t interview Groening or mogul James L. Brooks for his book. Much of this had to do with Ortved’s emphasis on the important role TV writing legend Sam Simon played in shaping the series and assembling its writing team in the first three years of the show.

Less bothersome to some reviewers is the fact that hardly anyone still involved with the show was interviewed (voice artist Hank Azaria being the primary exception), which is typical for any still-living Hollywood product. Should someone want to write the real Pixar story before the studio dries up (monetarily), they will face the same problems of dealing with the corporation’s front office before they can secure interviews with the talent.

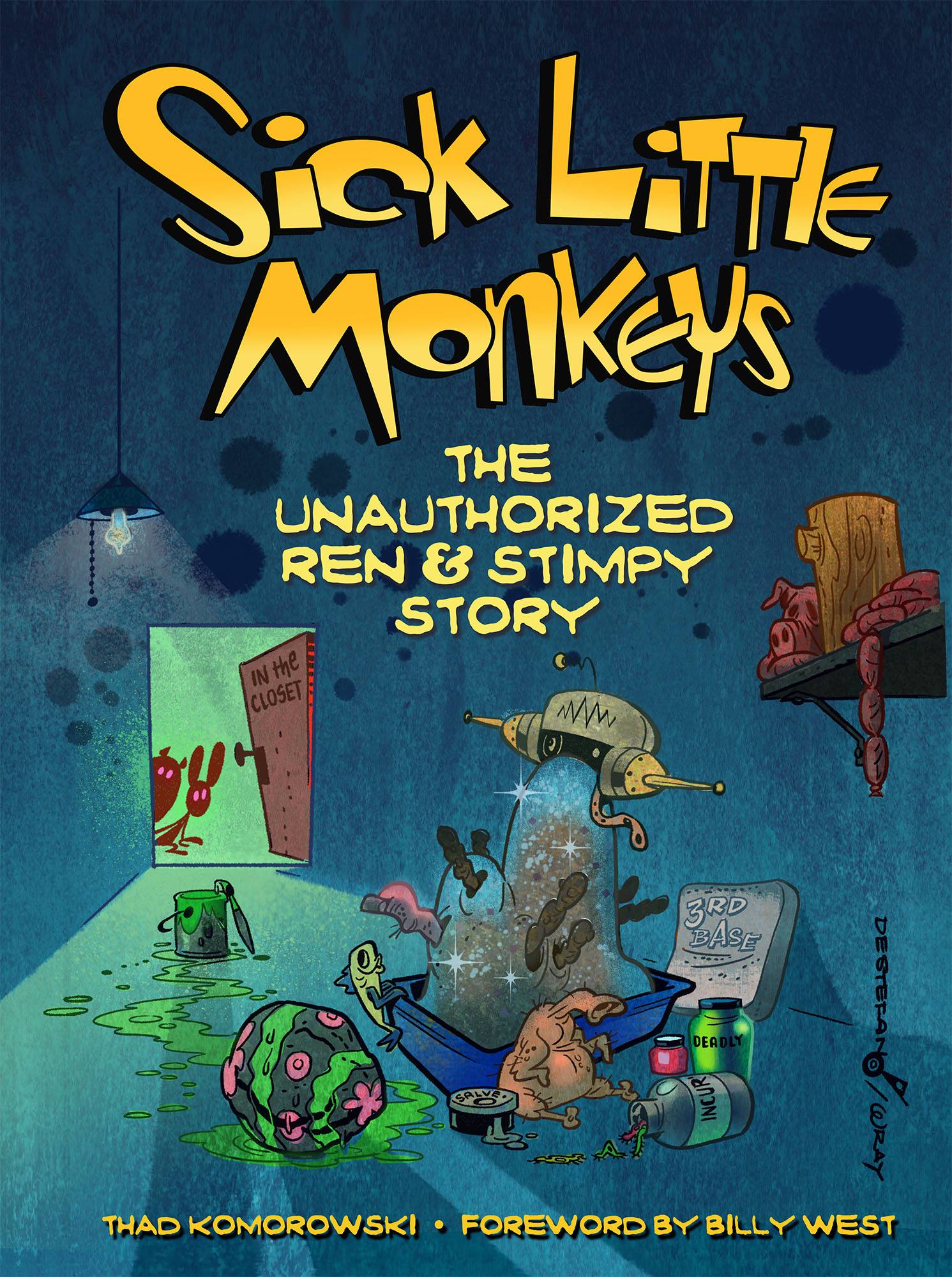

He quotes Groening and Brooks, albeit from a variety of sources, and was criticized that they weren’t able to answer to charges of their own egos in the present day, which seems to be a naive assumption at best. Anyone who honestly holds this against Ortved has obviously never conducted an interview with people in the entertainment business. Case in point: in preparation for my own book on The Ren & Stimpy Show, there were several notable people who refused to be interviewed, some declines more impassioned than others. More than once I was told that the accuracy of my reporting and writing is compromised because I’m a critic of John K.’s works and words. (They’re welcome to still be interviewed as of this posting.)

He quotes Groening and Brooks, albeit from a variety of sources, and was criticized that they weren’t able to answer to charges of their own egos in the present day, which seems to be a naive assumption at best. Anyone who honestly holds this against Ortved has obviously never conducted an interview with people in the entertainment business. Case in point: in preparation for my own book on The Ren & Stimpy Show, there were several notable people who refused to be interviewed, some declines more impassioned than others. More than once I was told that the accuracy of my reporting and writing is compromised because I’m a critic of John K.’s works and words. (They’re welcome to still be interviewed as of this posting.)

I’m sure Ortved was taught the same thing by his teachers in college that I was: there is no such thing as objectivity. Frequent use of “objectivity”, or “respect”, is symbolic of an individual whose aspirations for controlling what others think clouds his or her own reasoning. The best commodities of Hollywood always stem from powerful egos, and it’s only natural that people want to control how the history they lived is presented. Ortved said the big players would be fine talking to him if he would write a puff piece on the making of the Simpsons Movie. Likewise, regardless of my own attitudes and ardor, some people with R&S would have zero interest in contributing to anything more meaningful than the likes of the tame oral history (see the pattern?) that appeared in the most recent issue of Hogan’s Alley. Had Ortved actually interviewed the holdouts, they probably wouldn’t have answered the tough questions anyway.

All of which is to say that I certainly sympathize with Ortved’s plight, but I wish a better written book came out of it. There are endless hints throughout at how fascinating and wonderful a book about what was one of the most important TV shows of all time, and what was inarguably one of the few products of TV animation worth taking seriously, could be. Ortved laid the rough foundation, now it’s up to someone to utilize it. Maybe the show will actually be over by then.

It’s been over two years since the release of John Ortved’s

It’s been over two years since the release of John Ortved’s